In Medford, one of the cities that I work in frequently, downtown “revitalization” has become an issue of sorts in the local council races this cycle. It is encouraging that none of the candidates are opposed to spending money to support Medford’s historic downtown, they merely differ in what approach is most deserving of the city’s investment.

For many years Medford has approached downtown from what might be thought of as a big fix model. First it was investing millions of dollars into municipal parking structures, the theory being that improved parking would encourage shoppers to visit the area. There was an effort, in partnership with a local group, to develop an entertainment venue. Then there was another multi-million dollar parking structure and a half-dozen surface lots. There was the multi-million dollar venture to build first a new public library and then, in partnership with two local colleges, the Higher Ed Center. And now, in partnership with Lithia Motors, there is the Commons, a multi-million dollar office complex that will keep one of southern Oregon’s major businesses where it is, in downtown, in a new building, with new infrastructure and two new blocks of city parks. Sure, MURA has done other things, new sidewalks, railroad crossings and the Façade Improvement Grants (for which I am both thankful and the city’s designer) but the vast majority of its public funding has gone, and apparently will continue to go, to big ticket, big fix, projects. I am not at all sure that is best approach.

I have argued for over a decade that Medford would be better off investing $100,000 in ten places in downtown that actually encouraged visitors (and raised property values, but that’s another story), rather than investing $1 million in one location. Investing $14 million in the Commons (as they currently propose) is sort of epically out scale with what downtown probably needs, particularly given the fact that it is located in a distant corner of the area, largely surrounded by immovable historic buildings (the Elks Club, the Penney’s building), massive public works (the Bartlett St. Parking Structure), and a major road way, Riverside. IF the Commons is half as successful as its promoters contend, it can not help but suck the life out of the rest of downtown, an area that the City has been investing in and attempting to revitalize for nearly two decades.

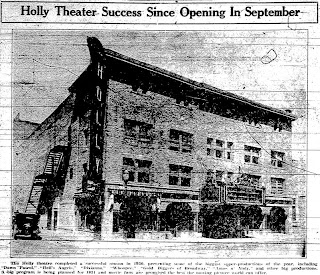

|

| Bartlett Street, most of which will be removed to create "The Commons." If it looks vacant, that's only because MURA bought most of the buildings and kicked out the tenants in anticipation of tearing them down. |

But not to worry… Lithia needs to remain in downtown and putting some gov’t funding into the project makes sense. But they won’t be building much to attract any other new investment or street activity any time soon. Lithia's own workforce is (thankfully) pretty stable, and so, while Lithia building themselves a new corporate HQ in downtown Medford is great news, it's highly unlikely to be the massive kick-start sto downtown success that Lithia and the City seem to think. The "Commons" is just the latest, and biggest, big ticket effort and, once again, will fail to revitalize Medford. The reasons are obvious. The Commons doesnt' create any new reason to go to downtown for anyone that doesn't already have to be there. Pretty simple, really, when you think about it, isn't it? Basically the Commons, as currently planned, fails the "feet on the street" test. Miserably.

Maybe next time I will write about what else, better, things MURA might do were it to invest less in the Commons. Here's a hint...it includes creating demand and putting more "feet on the street." But whatever happens, it will be interesting to see how, if at all, politics plays into downtown's future. At least downtown revitalization is on everyone's radar and that, for certain, is a positive trend.